Petroleum hydrocarbons are common soil contaminants that pose a risk to human and environmental health. Different analytical methods are used to determine their presence in soil, including non-specific screening techniques and lab-based fingerprint techniques. While the latter provides high accuracy, they can be time-consuming and expensive. Over the past decade, the emergence of various field analytical techniques, such as test kits and portable handheld devices, have enabled real-time petroleum hydrocarbons detection and measurement on-site, which has the potential to drastically reduce cost and time of analysis compared with traditional technologies and without sacrificing ‘Quality Management’ objectives. However, their performance for different soil types, contamination levels, and fuel types, as well as their ability to speciate and quantify different hydrocarbon groups for risk assessment, and their suitability for remediation monitoring and validation, have not been fully studied. It is also important to understand the type and quality of data that will be generated by field analytical technologies and interpretation of the data generated should be carefully evaluated before conclusions are drawn. Depending on which analytical technology is used, it is possible to achieve qualitative, semi-quantitative and quantitative results. In some cases, the accuracy of field analytical technology is approaching that achievable previously only from laboratory analysis. Yet, laboratory analysis may still be required to attain legally recognised measurements.

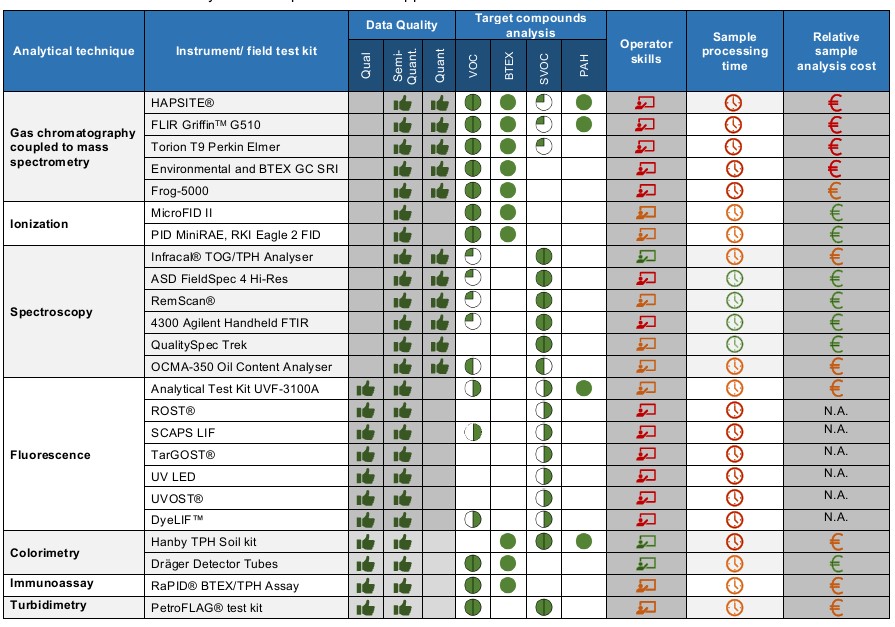

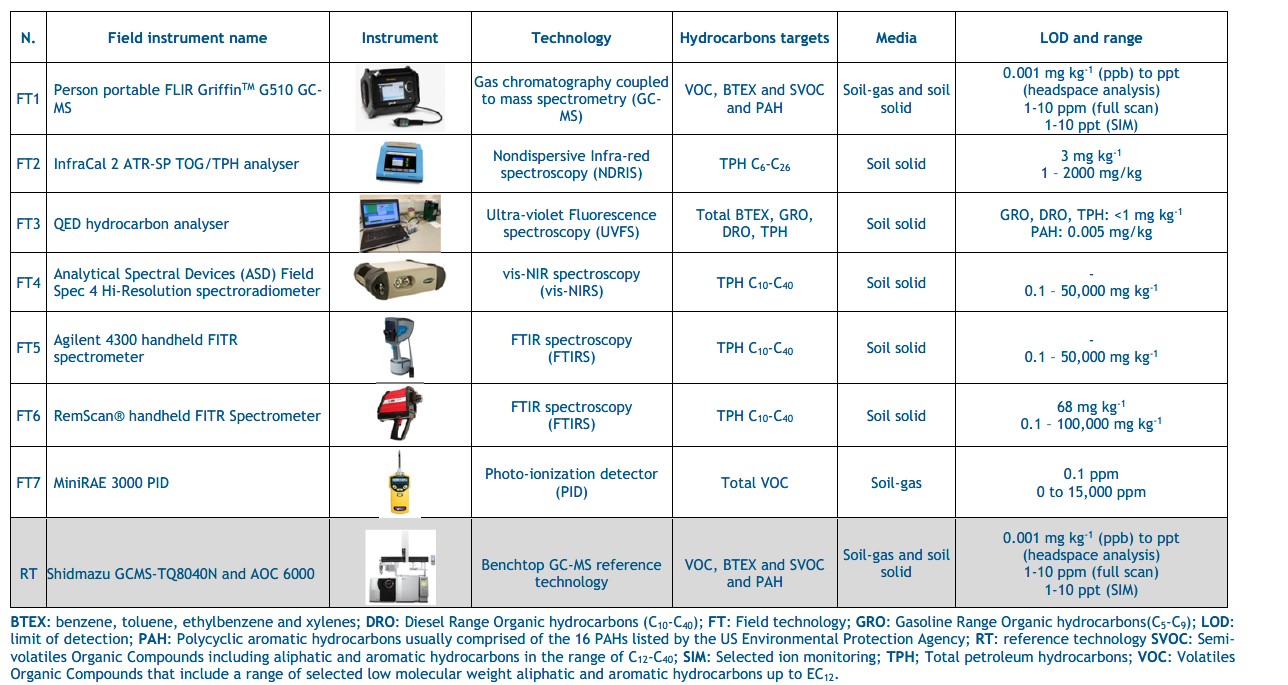

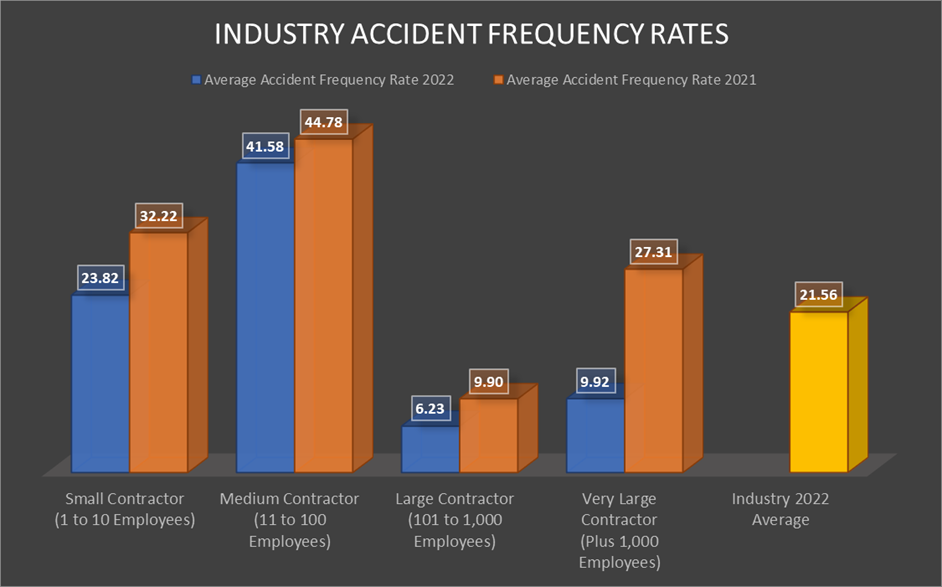

Figure 1: Summary of the criteria for selecting field analytical techniques for the analysis of petroleum hydrocarbon in soil

The main goal of this study was therefore to assess and raise awareness about the feasibility of using field-based techniques for determining TPH concentrations in soil, and whether they can replace lab processing. The study reviewed various techniques, ranging from high-end gas chromatographs and handheld infrared spectrometers to low-end oil pans and chemical kits. To ease comparison, the field analytical kits and devices were classified according to detection methods, target analytes detected and data quality levels (qualitative, semi-quantitative and quantitative) (Figure 1). The basic principle along the advantages and limitations of each field analytical technique, quality control requirements, operator skill level, and analysis cost are summarised and the synthesis can be accessed for free on the Concawe website at https://www.concawe.eu/wp-content/uploads/Rpt_21-3.pdf.

In general, the field analytical technologies for detecting petroleum hydrocarbons in soil are highly developed and well established. In terms of risk assessment, only GC-MS can accurately differentiate between aliphatic and aromatic petroleum fractions. However, this technique involves soil sample extraction and demands a high level of expertise, which may not be suitable for all projects. On the other hand, colorimetric, immunoassay, and turbidimetry test kits are cost-effective and rapid options for monitoring the reduction of petroleum hydrocarbons over time and guiding remediation strategies, but they lack specificity and do not provide information on individual analytes. Field spectrometry technologies offer real-time measurement of petroleum hydrocarbons in soil with minimal sample handling but require soil drying and cannot discriminate between aliphatic and aromatic fractions. Fluorescence technologies are used for in-situ site investigation with high spatial resolution but provide relative data and require skilled personnel. Both spectrometry and fluorescence systems can be useful in adaptive sampling designs to detect and predict contamination levels during the Phase 2 Investigation.

It is important to note that no single field analytical technology can quantify the entire range of petroleum hydrocarbons in soil, and therefore a combination of technologies may be necessary for greater accuracy in prediction.

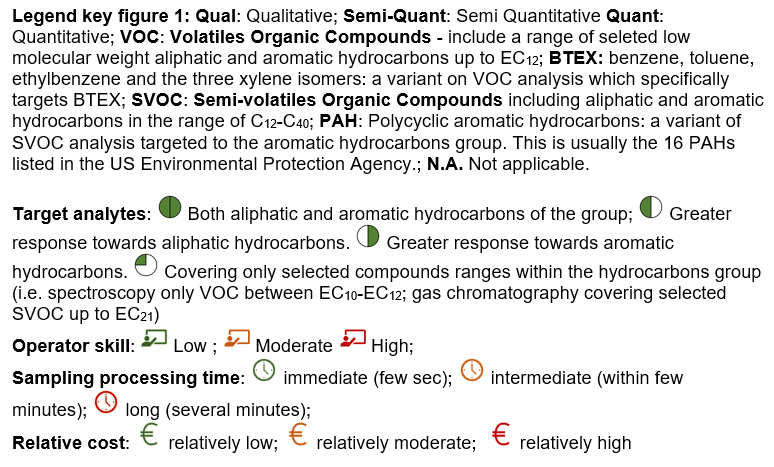

Figure 2: Overview of the field and reference technologies evaluated for petroleum hydrocarbons determination in soil

A representative subset of seven field-based technologies was then selected and tested with impacted soil samples, which were compared to results from accredited laboratory analysis [Figure 2]. The subset included 3 portable solvent-based technologies (one portable GC-MS (FT1), one portable nondispersive infrared (NDIR) spectrophotometer (FT2), one portable ultraviolet fluorescence (UVF) spectrometer (FT3)), and 4 handheld solvent free technologies (one handheld visible and near-infrared reflectance (vis-NIR) spectrometer (FT4), two handheld Fourier-transform infra-red (FTIR) spectrometers (FT5 and 6), and one handheld photoionization detector (PID; FT7)). Three soils (sandy loam, silty clay loam, and clay loam) were spiked with gasoline or diesel fuel on weight/weight basis to achieve 100, 1000 and 10,000 mg/kg spike levels.

All samples were analysed for Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH), Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), Gasoline Range organic (GRO) and Diesel Range organic (DRO) and speciated hydrocarbon compounds when the chosen technology allowed to do so. Gasoline spiked soils were not analysed with FTIR and vis-NIR spectroscopy as the use of methanol as preservative interferes with the analysis. It has also been reported that non preserved samples contaminated with gasoline are subject to volatilisation losses that occur during the analytical process which result in poor performance for such technique. The intra and inter spikes consistency were evaluated by determining (1) precision from triplicates expressed as the percentage of relative standard deviation (%RSD) and (2) bias which is the difference expressed as a percentage between the mean of the replicate measurements and the spiked theoretical concentration level. Similarly, performance comparison of the field technologies against a benchtop GC-MS technology was carried out by determining the difference (%) between the mean measurements determined by the benchtop GC-MS and the field technologies evaluated. Additionally, performance characteristics of the GC-MS were determined by analysing the certified reference material RTC-SQC026 in triplicate.

All solvent-based field technologies performed well for TPH determination in different soil types, while solvent-free non-invasive technologies showed higher variability and lower accuracy. Infrared technologies are influenced by soil characteristics, particularly for low-level spikes (<1000 mg/kg) and certain soil types. The portable GC-MS performed well and closely to the benchtop GC-MS. While the headspace analysis of the portable GC-MS was easy to use and allowed to save time compared to the benchtop GC-MS, extra analysis time was required for the soil extraction and analysis due to manual injection. The non-destructive and solvent free Fourier-Transform IR (FTIR) and visible and near-infrared reflectance IR (vis-NIR) spectroscopic technologies performed well with diesel and demonstrated to be versatile, fast, and easy to use approach, but the accuracy was lower than for other technologies when total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) levels were <1000 mg kg-1. The procedures for soil calibration and validation may further limit the FTIR and vis-NIR applicability for diverse soil type and fuel type. In comparison, the non-dispersive IR (NDIR) and UVF spectroscopy technologies showed better performance, typically ±15% precision and ±30% bias for quantifying TPH in soil, which meet regulatory requirements. The UVF technology also provided additional quantitative information into hydrocarbons groups which can inform swiftly remediation monitoring and validation. Analysis of soil-gas samples by photoionization detector (PID) showed that PID underestimated concentrations compared to both portable and benchtop GC-MS which was expected as PID only provides an indirect and approximate indication of concentration of volatile compounds (VOC) in soil. Nevertheless, the PID remains a valuable instrument for site risk screening of soil-gas vapours considering its low cost and ease to use. Complete report is freely available on Concawe website at https://www.concawe.eu/wp-content/uploads/Rpt.22-12.pdf

The authors are grateful to all members of the Concawe Soil and Groundwater Taskforce (STF-33) which include a wide team of collaborators and advisors across Europe for their useful discussions and contribution during the study progress and revision of the reports.

Article produced by

Markus Hjort1, Eleni Vaiopoulou1, Richard Gill1,3, Pablo Campo4, Célia Lourenço4, Chris Walton4 , Tamazon Cowley4, and Frederic Coulon4

1Concawe (Scientific Division of European Fuels Manufacturers Association), Brussels, Belgium

2ExxonMobil (Esso Petroleum Company Limited), Avonmouth Fuels Terminal, St. Andrews Road, Avonmouth, Bristol, BS11 9BN, United Kingdom

3Shell Global Solutions International B.V., Carel van Bylandtlaan 30, 2596 HR, The Hague, Netherlands

4Cranfield University, School of Water, Energy and Environment, Cranfield, MK43 0AL, UK