Continued data sharing with the AGS into 2024 not only reinforces the importance of transparency but also enhances the industry’s shared understanding of safety performance. As more organisations participate, the resulting datasets will provide a valuable basis for collaboration across the geotechnical and geoenvironmental sectors, empowering targeted interventions and informed decision-making. This growing culture of reporting helps uncover hidden risks and promotes shared accountability. By embracing safety as a collective priority, the industry can progress beyond compliance, cultivating a proactive, learning-driven environment where wellbeing is central to operational excellence.

2024 Accident Incident Data

The data collected by the AGS highlights key safety patterns. Some entities show notably high volumes of hazard observations, which may reflect either strong reporting mechanisms or areas of elevated risk. Consistently high levels of minor injuries, near misses, and hazard reports in certain areas suggest an increased exposure to risk or a robust internal reporting culture. Meanwhile, spikes in near misses and minor injuries elsewhere point to opportunities for focused safety interventions. On the opposite end, some reporting environments show minimal incidents across all categories. This could indicate genuinely low-risk conditions or potential gaps in reporting behaviour.

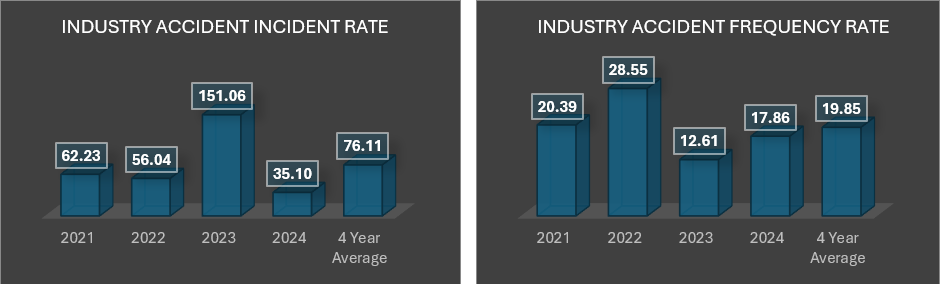

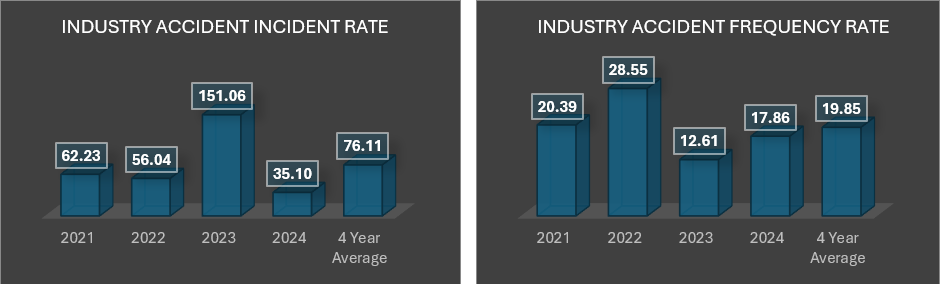

To facilitate the evaluation against HSE statistics and ensure consistency with industry standards as reflected in last year’s published data, the same two accident incident rate metrics have been applied in calculating the 2024 figures;

Accident Incident Rate (AIR) – (number of RIDDOR reportable accidents / average workforce headcount) x 100,000.

Accident Frequency Rate (AFR) – (total number of harm accidents / total number of hours worked) x 1,000,000.

AGS AIR Analysis

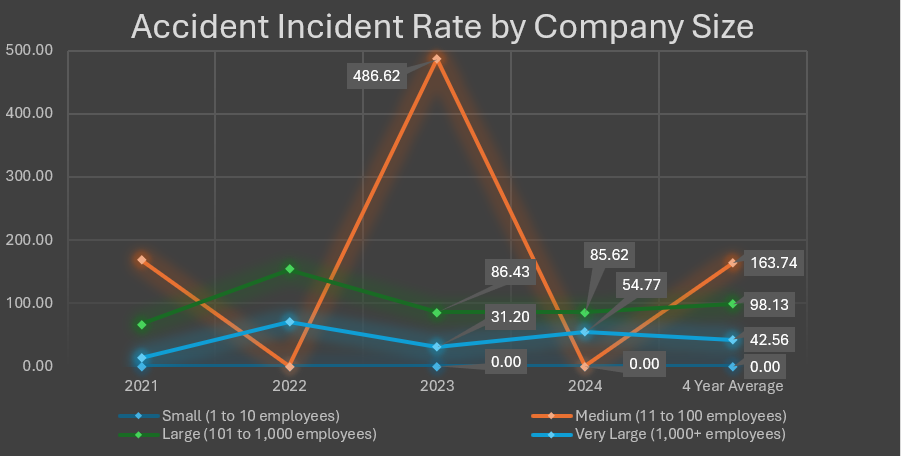

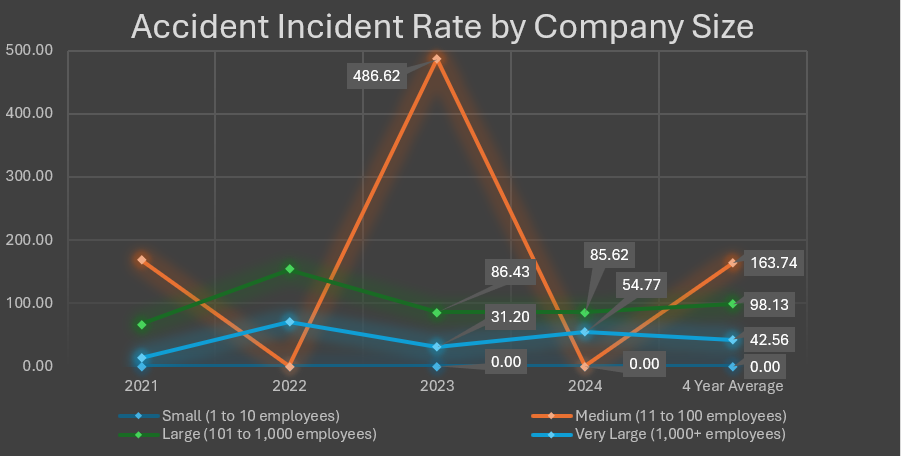

An analysis of Industry AIR across varying contractor sizes from 2021 to 2024 reveals critical insights into workplace safety practices and reporting behaviours. Small contractors, employing 1 to 10 individuals, recorded zero RIDDOR Reportable incidents throughout the four-year period. It is worth noting that the AIR calculation does not include the single fatality involving one of the smaller contractors. Medium-sized firms (11 to 100 employees) displayed striking volatility, with sharp peaks in 2021 and 2023 but no reported data in 2022 or 2024. This inconsistency raises questions about engagement levels and potential systemic gaps. Large contractors (101 to 1,000 employees) maintained a steady presence, contributing moderate incident rates year after year and suggesting more robust reporting mechanisms. Very large contractors (1,000+ employees) exhibited a gradual increase, starting from low and rising incrementally, possibly indicating progress in internal accountability. While medium contractors registered the highest average incident rate across the period, the persistent silence from smaller firms points to an urgent need for improved safety visibility and inclusive reporting practices.

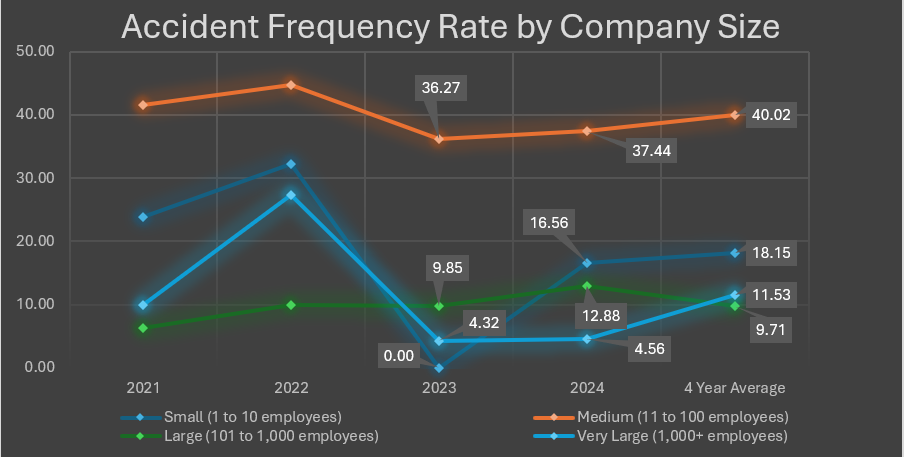

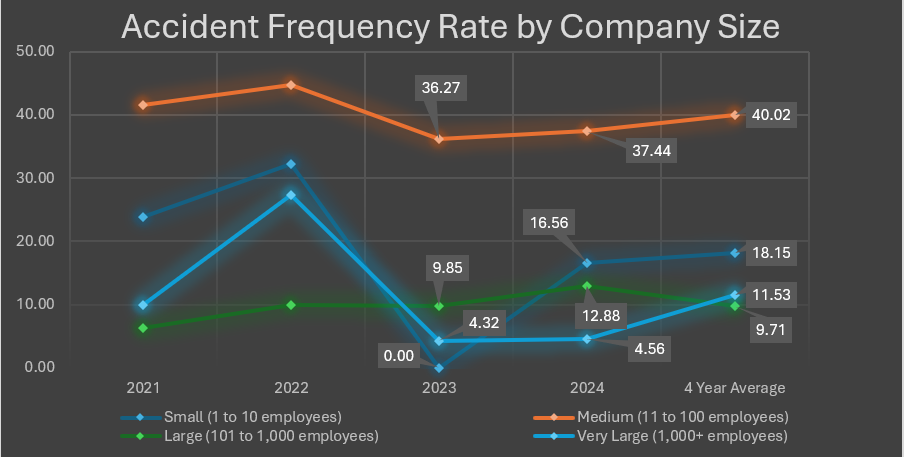

AGS AFR Analysis

From 2021 to 2024, Industry AFR’s varied significantly across contractor sizes. Medium-sized contractors (11 to 100 employees) consistently recorded the highest rates, averaging 40.02, with a peak of 44.78 in 2022. Large contractors (101 to 1,000 employees) maintained the lowest and most stable rates across all years, averaging just 9.71, suggesting stronger safety systems or controls. Very large contractors (over 1,000 employees) showed irregular performance, spiking in 2022 before stabilising, while small contractors (1 to 10 employees) exhibited inconsistent reporting, with a surprising drop to zero in 2023 and a four-year average of 18.15. These trends highlight a need to strengthen safety practices among medium-sized firms and improve support for both very small and very large organisations.

When comparing the AIR to the AFR for 2024, the most striking takeaway from the visual data is the 76% marked decline in the number of serious incidents relative to 2023. At the same time, a 41% rise in reported minor injuries suggests that safety interventions are gaining traction and that reporting practices have improved significantly. Together, these shifts point to meaningful progress in both the implementation and documentation of workplace safety measures.

That being said, only 68.57% of the AGS survey data responded “Yes” to capturing both positive and negative observations or hazard spots, suggesting just two-thirds of organisations actively engage in monitoring and recording workplace safety behaviours and conditions. 31.43% of organisations either do not capture this type of data or have failed to confirm they do, and only 27% of small companies have responded “Yes”. These figures also reinforce the need for tailored support for very small companies and self-employed businesses, where current engagement appears especially limited.

‘There is a clear opportunity to strengthen safety culture and improve reporting systems across the sector.’

The Construction Industry

Non-Fatal Workplace Injuries – In the latest reporting year, 4,050 non-fatal injuries to employees in the construction industry were documented by the HSE, with 2,518 classified as reportable under RIDDOR. These injuries typically involve incidents that result in hospitalisation for more than 24 hours or an inability to work for seven consecutive days. Slips, trips, or falls emerged as the most common cause, accounting for 972 cases (24% of all non-fatal injuries) and contributing to 20% of reportable incidents. Falls from height followed closely with 807 cases (20%), responsible for 12% of all reportable injuries. Manual handling, lifting, or carrying led to 742 injuries (18%) and represented the largest single contributor to over-7-day absences (25%). Other notable categories included injuries caused by moving objects (481 cases, 12%) and contact with machinery (261 cases, 6%), both associated with extended recovery periods.

Fatal Workplace Injuries – Recent HSE data on fatal workplace injuries reveals enduring safety challenges in high-risk sectors, particularly among self-employed workers. Of the 51 recorded fatalities, 28 involved self-employed individuals. Falls from height were the most frequent cause, accounting for 31 fatalities, with nearly two-thirds affecting those who work independently. Other significant risks included being struck by moving vehicles and incidents involving collapse or overturning of structures, both disproportionately impacting the self-employed.

Key Concerns

While the recorded fatality count across the AGS organisations remains low, with only one fatality documented, the prevalence of minor injuries, near misses, and hazard observations indicates persistent underlying risks in workplace environments. Several organisations show zero or near-zero reporting across all safety categories, raising flags around potential underreporting, disengaged safety cultures, or gaps in audit structures. Additionally, while hazard observations are frequently high, environmental incidents remain comparatively low across most organisations, pointing to either successful hazard mitigation strategies or limitations in how environmental risks are captured and classified.

Our own analysis of the Accident Incident Rate (AIR) data highlights a pressing concern: smaller companies, often comprised of self-employed individuals, show significantly weaker safety outcomes. This disparity underscores the urgent need for targeted interventions to improve safety standards and support within this group.

Industry Safety Culture

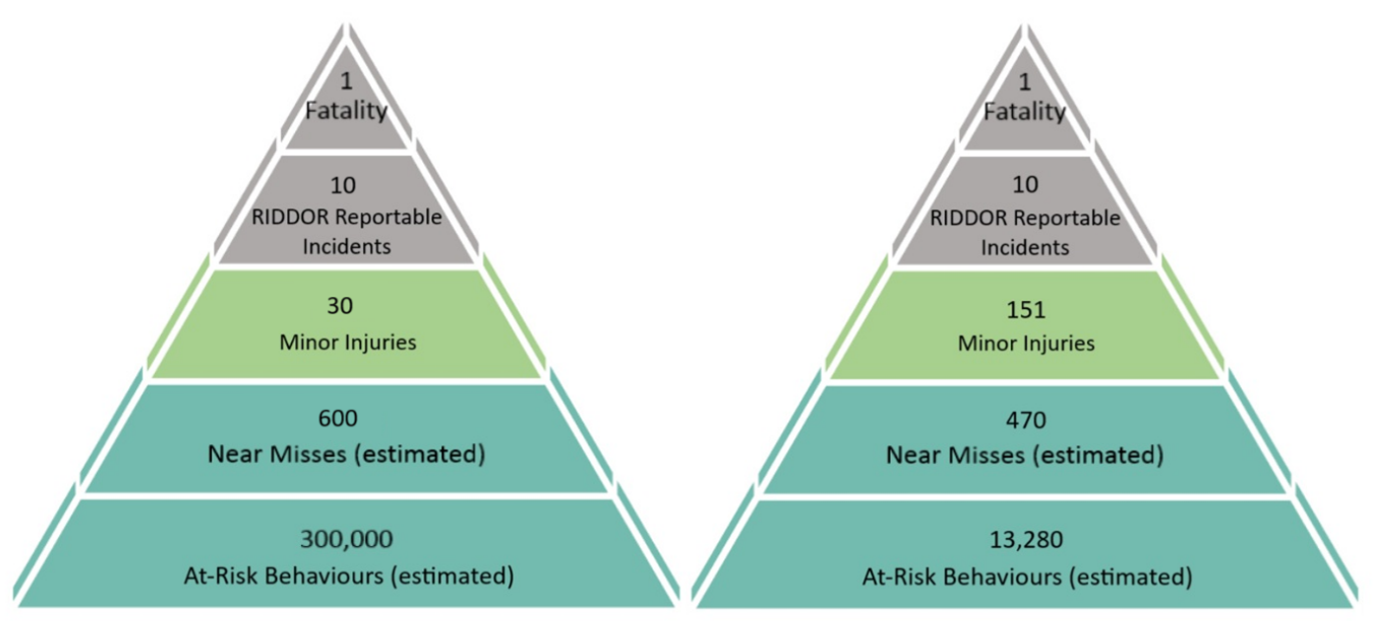

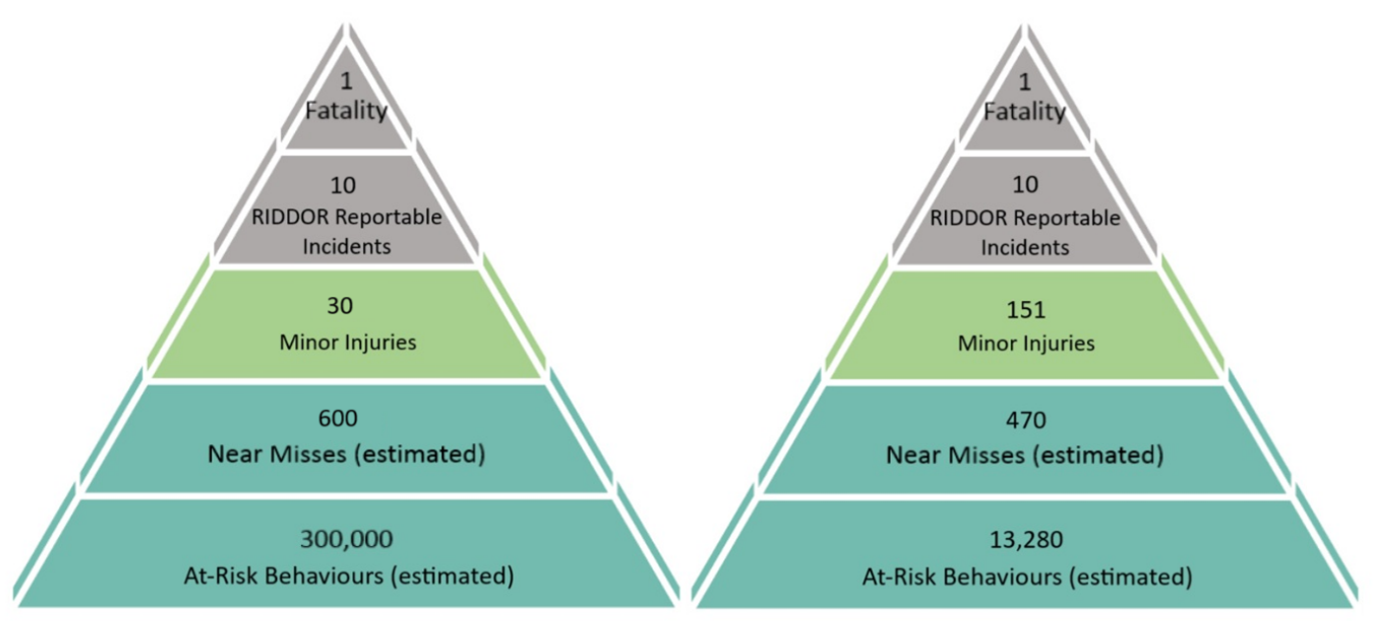

The Safety Triangle has been used to evaluate organisational safety culture and demonstrate the proportional relationship between incident types. Its application supports consistency in statistical reporting across multiple years. According to the model, for every fatality, there are approximately 10 lost workday cases, 30 minor injuries, 600 near misses, and an estimated 300,000 unsafe behaviours, highlighting the importance of addressing lower-tier events to prevent serious outcomes.

The following graphic compares the Safety Triangle with real-world data provided by the AGS, highlighting key differences in incident ratios and reporting trends:

The contrast between the theoretical safety pyramid and the AGS data highlights both consistency and deviation. While the core principle remains valid (serious incidents often arise from a wider foundation of less severe occurrences), the ratios in the AGS dataset are notably more condensed. In place of the traditional model’s 600 near misses and 300,000 unsafe acts leading to a single fatality, the AGS data triangle presents just 470 near misses and 13,280 at-risk behaviours. This difference further highlights the ongoing need to improve how unsafe acts and near misses are reported across the industry.

‘Consistent and comprehensive documentation of At-Risk Behaviours and Near Misses remains an area requiring attention’.

AGS and BDA Collaboration

The AGS and BDA, recognised as two key bodies in the ground investigation sector, are enhancing their partnership – an encouraging development marking a step forward in industry-wide collaboration. When benchmarking safety outcomes, it is important to recognise the differences between their datasets.

- BDA members are primarily operational drilling contractors, working in environments that involve mobile plant, variable site conditions and manual labour, all of which carry higher inherent risk.

- In contrast, AGS membership encompasses a broader spectrum of the geotechnical and geoenvironmental sector, including organisations often operating in lower-risk, office-based or controlled settings.

This distinction contributes to the lower AIR and AFR figures reported by the AGS. While this data shows stronger trends in minor injury and hazard reporting and indicates a more developed reporting culture in some areas, the reduced use of heavy plant makes direct comparisons with BDA data challenging. These differences highlight the need for more specific benchmarks to ensure fair and meaningful evaluation across the industry.

Currently, 22% of AGS members are contributing to data sharing initiatives. While overall membership has grown, this marks a 5% decline in participation compared to 2023 figures. This shortfall underscores the urgent need to expand data sharing efforts, not just for broader engagement, but to strengthen the accuracy and reliability of industry-wide datasets. Enhanced participation is critical to improving the precision of statistical analyses, which in turn adds meaningful value to reported figures. With more robust and representative datasets, the industry can better identify and respond to specific health and safety challenges, accelerating targeted interventions and fostering more consistent, data-driven reporting standards.

Summary

The 2024 accident statistics for the geotechnical and geoenvironmental industry reveal encouraging progress in safety reporting and intervention. Serious incidents have dropped by 76% since last year, while minor injury reporting rose by 41%, suggesting improved engagement and transparency. However, disparities persist, particularly among small contractors and self-employed workers, where underreporting and elevated risks remain concerns. The data provided highlights the need for stronger safety cultures and tailored support across all contractor sizes.

Article provided by Rachael Parry TechIOSH CMgr MCMI, Geotechnical Engineering Ltd Operations Support Manager